The city and film, a love story

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready... |

From Buenos Aires to Casablanca, urban space has been imagined in a thousand ways. Films are a mental map of the city – a source of myths, aspirations and nightmares – and help us to imagine the idea we have of it.

They were born and grew up together throughout the 20th century. Cinema and the modern city, the greatest popular art and the most important form of social organisation, have many things in common: both are relatively recent inventions, both experienced accelerated growth, and both were left for dead more than once.

From the beginning, the relationship between them was inseparable. Films help us imagine cities, and sometimes their images are more real than the cities themselves.

“Entire cities have been defined by their cinematic representations; to the casual viewer, Vienna is a smuggler running through a maze of torchlit or moonlit sewers, Tokyo is a panorama of aeroplane lights, crosswalks and skyscrapers shot from the Park Hyatt hotel, and Casablanca is a fog-laden airport or a jazz club frequented by military men, at once reactionary and ambiguously resistant,” explains Irish writer Darran Anderson.

In his formidable book Imaginary Cities, Anderson recalls that when John Carpenter set out to film Escape from New York – a 1981 film that chronicles the conversion of the metropolis into a huge, lawless prison – he found the perfect location in the streets and factories of East St. Louis. The city had been abandoned to its fate by industry and the authorities, who nevertheless were happy to help by turning out the city lights to accentuate the hopeless atmosphere they had already created.

What is fact and what is fiction in Robocop, Paul Verhoeven’s brilliant satire set in a broken Detroit, written 23 years before Michigan’s most populous city declared bankruptcy? Is the London of Children of Men, with illegal immigrants in cages and millionaires inhabiting posh security compounds, a pessimistic picture of the future or the present barely exaggerated?

The city as a character

“The city is a living presence… almost a character”.

The phrase comes from Bruno Stagnaro, director of the new adaptation of El Eternauta that is being filmed these weeks. The comic strip by Oesterheld and Solano López left indelible images of the General Paz highway, River’s stadium and Belgrano’s barrancas. How will the director of Okupas imagine them? Will the toxic snowfall in Buenos Aires be inspired by the lines of the comic or by the images of 9 July 2007, the day when it actually snowed in the capital? Interesting feedback phenomenon: fiction imitates reality, which in turn imitates fiction.

The power of post-apocalyptic images lies in the fact that they generate an alienating effect on viewers.

Hugo Santiago’s Invasión – the second best Argentinean film in history according to the most recent survey of Argentinean cinema – tells the story of Aquilea, a city “besieged by powerful invaders and defended – it is not known why – by a group of civilians”, as defined by Jorge Luis Borges, one of its screenwriters.

“Its plan, shown several times, is a stylisation of the outline of Buenos Aires”, wrote Edgardo Cozarinsky shortly after its premiere in 1969. The maps emulate it and the images of esplanades and piers, low-lying areas and skyscrapers refer to the Buenos Aires landscape, but the arrangement of the elements and some omissions suggest a completely new universe. “The city that the film explores is like a shorthand of more complex, absent signs, but at the same time it subscribes in those who know Buenos Aires a double astonishment of recognition and strangeness”. It is and it is not, you know what I mean.

We discussed this over coffee with Adrián Pérez Llahí, assistant professor of Media History at the Universidad Nacional de Lanús (UNLa).

Adrián is doing his PhD on the treatment of urban space in Argentinean cinema in the 1960s, and so far he has found three well-defined spaces in the films of the period: the centre, the neighbourhood and the outskirts.

“The lights of the centre are synonymous with perdition, the place where the protagonist’s morals are at stake. The neighbourhood is the cheap houses of Liniers or Barracas. And the outskirts are not the suburbs that we see today in Raúl Perrone’s films, but a place far from the city, represented in the isolated house or the patrician mansion”, he enumerates.

Cinema also witnessed the growth of the urban sprawl. At the beginning of Fernando Ayala’s 1958 film El Jefe, the character played by Alberto de Mendoza leads a group of criminals who pose as auctioneers and set up a fake land lottery. Prisioneros de una noche, a film with Alfredo Alcón shot four years later, starts from the same premise: a land auction in the suburbs.

This conflict over urban space, a finite asset whose limits are the laws and regulations, is also transferred to the city itself, where the phenomenon of horizontal property is consolidating. “The problem is not that people are destroying but that they are building, that buildings are being constructed where there were none before,” says Adrián. “This generates an economic problem and a problem of coexistence, summarised in the figure of the party wall”.

For this researcher, the film of the sixties is not the first Argentinean cinema to show the city, but it was the first to deal with new themes such as life in the peripheries, the densification of the urban nucleus and even the role of hotel accommodation in the framework of a battle for intimacy. “When you go out to film, no longer in studios but in real locations, it’s impossible not to have to face the material problems of space management,” he concludes.

The city as a laboratory

Speaking of real locations, you may have noticed that drones brought back into fashion aerial shots, which had accompanied fictional cinema since its origins.

For Teresa Castro, professor of film studies at the Sorbonne Nouvelle University, this was because aerial views not only portrayed and described large urban centres but also contributed to giving them a spectacular dimension.

From the air, there is nothing surprising about a field or a farm. But a city… a city is something else. Austrian director Fritz Lang says that one of his great classics was born out of his fascination with the skyscrapers of New York: “I looked at the streets – the dazzling lights and the towering buildings – and there I conceived Metropolis”. An aesthetic of the panoramic gaze linked to a love of vertigo and heights, the same aesthetic that a few years later helped King Kong to turn the Empire State Building into a cultural icon.

In parallel, a more rational-scientific factor emerges, linked to the technological advances of the Great War: “Aerial photography became an official means of cadastral representation, seducing architects, urban planners and geographers as a way of reading and understanding the scale and size of modern metropolises,” Castro argues. This role changed after World War II. Aerial images continued to convey distance and beauty, “but at the same time reminded us of the new status of the urban environment as a military target, while becoming more intimately linked to planning and social control.

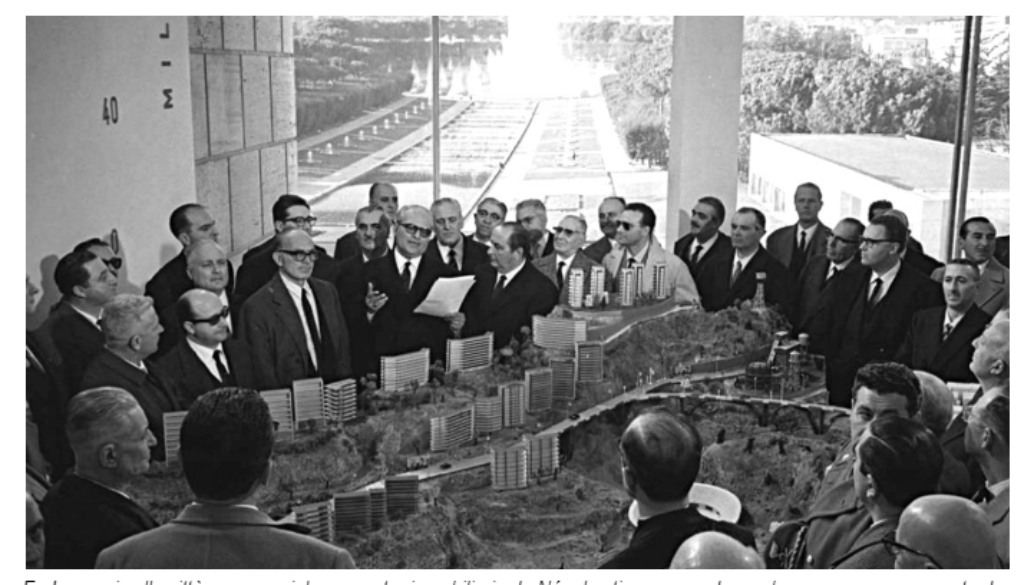

Something similar happened with the maps of cities. In Le mani sulla città (1963), a brilliant film by Francesco Rosi, the map and the model are devices of power. The film chronicles the attempts of a certain Nottola, a ruthless property developer and elected councillor of Naples, to push for the urban development of a series of plots of land on the outskirts of the city.

The fact that the Neapolitan region, with its unstable geological conditions, is not an ideal site for his plans matters little to Nottola, who pushes ahead with his project while shielding himself from criticism from politicians and the press. An intertitle clarifies: “The characters and events narrated here are fictitious, but the social and environmental reality that produces them is authentic”.

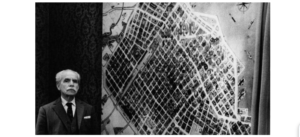

At almost the same time, but on the other side of the ocean, a brutal urban transformation was taking place, embodied in the figure of Robert Moses, the urban planner responsible for the motorway system that destroyed entire neighbourhoods in Brooklyn and the Bronx.

In Motherless Brooklyn, a film directed by and starring Edward Norton, Moses is played in villain mode by Alec Baldwin. In his office on Randall’s Island, Moses/Baldwin appears in front of a gigantic map of New York. There, with a pencil, the planner used to make “big sweeping gestures on the map, or sharp, precise jabs at it as he imagined the possibilities,” says journalist Robert Caro, author of a monumental biography of this character who made and unmade the city as he pleased.

The city as a stage set

In London’s Notting Hill, a must-see for film buffs is the front door of Hugh Grant’s house in the film of the same name. Visitors to Edinburgh can take one of the many Harry Potter tours. The list goes on: there is a ghostly presence of Harry Lime in Vienna or Amélie in Montmartre: “Since the stars themselves are either dead or unreachable, locations must be second best,” say François Penz and Richard Koeck in a book on the relationship between the seventh art and geography.

But the elusive aura of these characters can only disappoint modern tourists and other experience collectors. Without the chemistry of Jessie and Céline (the couple in Before Sunrise), Vienna’s Westbahnhof is not the start of a romantic adventure but barely a train station in Austria; without the Cold War world (portrayed in spy films like The Man Between), Checkpoint Charlie is little more than a tollbooth where they sell fake pieces of the Berlin Wall.

One of the many powers of cinema is to give the city a unique and unrepeatable role. What our Instagram accounts don’t seem to understand is that it’s impossible to re-edit those moments in a touristified portion of urban space.

PS: I suggest you watch the films, they all have something to say about the relationship between cinema and the city. Robocop and Le mani sulla città are on Amazon Prime Video. King Kong and Before Sunrise are on HBO Max. Motherless Brooklyn is on HBO Max and Amazon Prime Video. Prisoners of a Night is on AR CINEMA. The Boss is available on YouTube. The other films listed are available… over there.

By Federico Poore, CENITAL journalist.

This article was originally published on 10 May 2023 in CENITAL.