Urban cable cars: mobility and social integration from the heights

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready... |

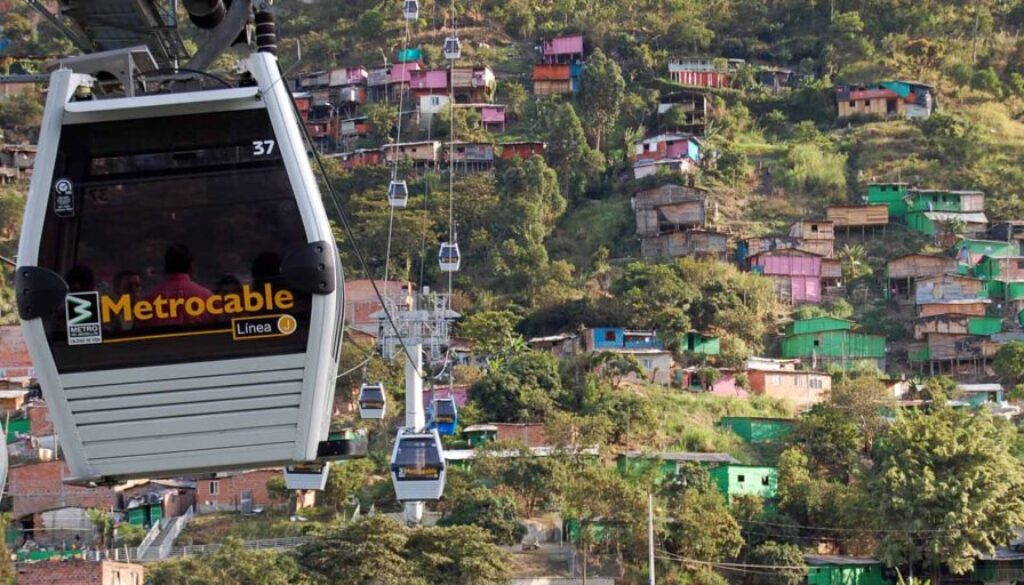

How to link vulnerable neighbourhoods to the city centre when mountains literally separate them? At the beginning of the 21st century, a Colombian capital found a mobility solution that was soon replicated in other rugged areas of Latin America. With different characteristics, the premise is the same: reducing physical distances shrinks social distances.

For many decades, Medellín (Colombia) was a city hit by crime and organised violence. As a consequence of forced displacement, informal settlements multiplied year after year on the hills and hills of the periphery. These “invasion neighbourhoods”, as they are known in the Caribbean country, grew without planning or any kind of public services. “They are made up of homes built by their own inhabitants. Their connection with the rest of the city was practically non-existent”, says urban sociologist José Ariza de la Cruz.

Everything changed in 2004 with the opening of the Metrocable as the world’s first aerial tramway. Until then, cable cars had only been used for commercial reasons – for mining activities, for example – and for tourism in mountainous areas. But the experience in the capital of Antioquia marked a before and after in urban public transport, and its experience was soon replicated in cities with similar characteristics.

“The system made it possible to connect high areas where it is impossible to build transport such as the metro or where the bus hardly reaches due to the irregularity of the streets and the high density of housing. It is cheap and very fast,” explains specialist Ariza de la Cruz. In addition, it integrated impoverished neighbourhoods with the city’s traditional mobility system, especially the metro. Thus, journeys that took more than two hours (and multiple tickets) were reduced to 30 minutes with a single ticket.

Documented benefits

In 2019, the Medellín Metrocable was distinguished by the WRI Ross Award for Cities as an innovative solution for urban integration. According to its analysis, it was the driving force behind one of the largest urban transformations ever experienced in Latin America. Underprivileged communities, which were once immersed in violence and disorder, were transformed into renewed and serviced neighbourhoods.

“Libraries, schools and parks have been built in areas where public investment used to be absent. People are now in public spaces to play and socialise, and commerce is thriving. Access to jobs and other opportunities has also increased,” said researchers Madeleine Galvin and Anne Maassen.

Based on a documentary compilation of research, sociologist Ariza de la Cruz listed the many benefits Medellín experienced thanks to the Metrocable. “The first line caused a 66% decrease in homicides in the neighbourhoods it reached. It increased confidence in public institutions, such as the judicial system and the police,” he said.

In particular, experts emphasised that by connecting the most precarious areas of the city with the rest of the neighbourhoods and facilitating population exchange, the cable cars helped to reduce social stigmas. “Ultimately, by reducing physical distances, it reduces social distances. Public transport is very important in combating the inequality and segregation inherent in the historical development of cities. Its contribution to weaving its different parts together is invaluable,” said Ariza de la Cruz.

With a total length of nearly 15 kilometres and more than 14 million annual passengers, the Medellín Metrocable is also recognised for contributing to the reduction of traffic accidents and carbon emissions.

The largest and highest

Inspired by the experience of the capital of Antioquia, several Latin American cities replicated the model and adapted it to their rugged geography. Bogotá, Manzanares and Cali (Colombia), Rio de Janeiro (Brazil), Caracas (Venezuela), Guayaquil and Durán (Ecuador), as well as other localities that have ongoing projects.

But one city stands out internationally for having created the system that transports the largest number of people (42 million a year). It is also the longest (33 km interconnected) and the highest on the planet. This is “Mi Teleférico”, which links La Paz (at 3,600 m above sea level) with El Alto (at 4,100 m above sea level).

Inaugurated in 2014, it was born as a necessity to provide a solution to the mobility problems in the metropolitan area of the Bolivian capital. Existing services were unable to cope with the growing demand of users, traffic was becoming increasingly chaotic and environmental pollution was on the rise. In particular, El Alto had experienced exponential population growth over the past decades: from 11,000 inhabitants in 1950, it surpassed one million in 2017, making it the largest large city in the world.

“Cable cars used to be used for tourism and thanks to someone who dared to think differently in Medellín, today they are an innovation in urban transport. Medellín has been like the big brother we’ve had; we’ve visited its Metrocable many times,” said César Dockweiler, then executive manager of Mi Teleférico, in 2018.

The Bolivian solution won the LATAM Smart City Award that year as a good practice in sustainable urban development and mobility. Today, it is the main means of public transport in the metropolitan area of La Paz; it has urban lifts, underground stations, connecting bridges and public meeting spaces.

This note was originally published on 30 January 2023.